Creativity for children is actually a complicated, rather elegant set of skills. But one simple skill lies at the heart of children’s creativity—divergent thinking.

Understanding divergent thinking has really helped give the teacher and parent in me a starting place from where to see each of my kids’ own creative capacity. And, it has helped me design easy, powerful learning for the long haul. And, they’ll need creativity not only to invent new things but for the problem solving we know will be required of their generation.

There are two essential types of thinking that help us solve problems and bring new ideas to life: convergent and divergent. Our kids will surely need to develop both convergent and divergent thinking skills to address an ever-changing world full of challenges. But only one of them is supported by schools and dominant culture today. Let's talk about why they both matter and what we can do to ensure our kids have strength on both sides of the creative thinking coin.

Convergent thinking

In convergent thinking, you select or “converge” around the best answer to a given problem. With as much speed and accuracy as possible, you focus in and try to view things as black or white, right or wrong. The aim is to land on the most effective solution or idea.

In school settings, kids use convergent thinking when they answer questions like “What is 5+5?,” respond to multiple choice prompts, or complete tasks with a single, correct outcome. Convergent thinking is also essential to the myriad decisions we all make every single day, like what we're going to make for dinner, what to wear, and which errands we'll actually get done.

Divergent thinking

“Divergent thinking is the center of human creativity.”― Amit Ray

On the opposite end of the spectrum, we have divergent thinking. Rather than honing in on a single, correct answer, divergent thinking allows us to generate the greatest number of ideas. Divergent thinking is therefore a core component of creativity—this ability to generate fuels our ability to create.

In school settings, we use divergent thinking to answer questions like “? + ? = 10.” Even though the underlying math is the same as “2+2,” the question, asked this way, can lead to multiple answers, making it a perfect prompt for divergent thinking. Ask kids to imagine new characters and stories, or give them loose parts and the time to create with them, and they’ll readily put divergent thinking to work.

“There is no doubt that creativity is the most important human resource of all. Without creativity, there would be no progress, and we would be forever repeating the same patterns.”—Edward de Bono

The problem

As a culture, we tend to be great at convergent thinking, and we get better and better at it as we age. But our capacity for divergent thinking tends to fall off a cliff shortly after we reach school age.

These trends make a lot of sense given how life works today. Most formal schooling in the U.S. is focused on tasks with one right answer (again, 5+5=?). Our grading system tends to incentivize students to work toward whatever answer will get them an “A,” rather than encouraging them to think outside the box.

A recent study by Pediatrics shows that children are given far less free time to play both at school and at home. Instead of open-ended, generative play, kids are spending more and more time drilling skills with tutors, practicing instruments with precision, or honing athletic performance. Even though math, music and sports can all be wonderfully creative endeavors, kids tend to be rewarded for getting the correct right answer as quickly as they can, nailing the note or scoring the most points.

It’s not surprising that our capacity for divergent thinking declines with age. When researchers Dr. Leonard Brzozowski, George Land and Beth Jarman asked kindergartners how many ways they could use a cup, a pencil, or a shoe, each child gave up to 100 valid answers. When 10-year-old children took the test, their scores showed a 60% drop.

“Logic will get you from A to B. Imagination will take you everywhere.”—Albert Einstein

The good news

Humans start out being rather marvelous at divergent thinking. Some early results from assessments like the Unusual Box Test suggest this ability is already brewing in infants and toddlers, while additional research shows it practically exploding in children ages 4 to 6. We've long known that 90 percent of brain development happens in the first five years, so as parents and teachers, we need to use this magic window wisely. Simply give your little ones continuous opportunities to practice divergent thinking and you can help them boost their creativity. Here's how to start.

5 ways to encourage divergent thinking today

1—Give kids time for free, open-ended play! Get them off screens and into situations in which they’ll need to use objects in different ways. If you’re in need of inspiration, you can visit our activities page for more than 100 easy ways to prompt open-ended play in the best creative space of all—the outdoors.

2—Try the “cup challenge.” Hand your kid a cup and ask, "What can you do with this?" Once they show you, ask, “What else can you do with it?” Keep going to see how many answers they can come up with—and how many you can come up with, too.

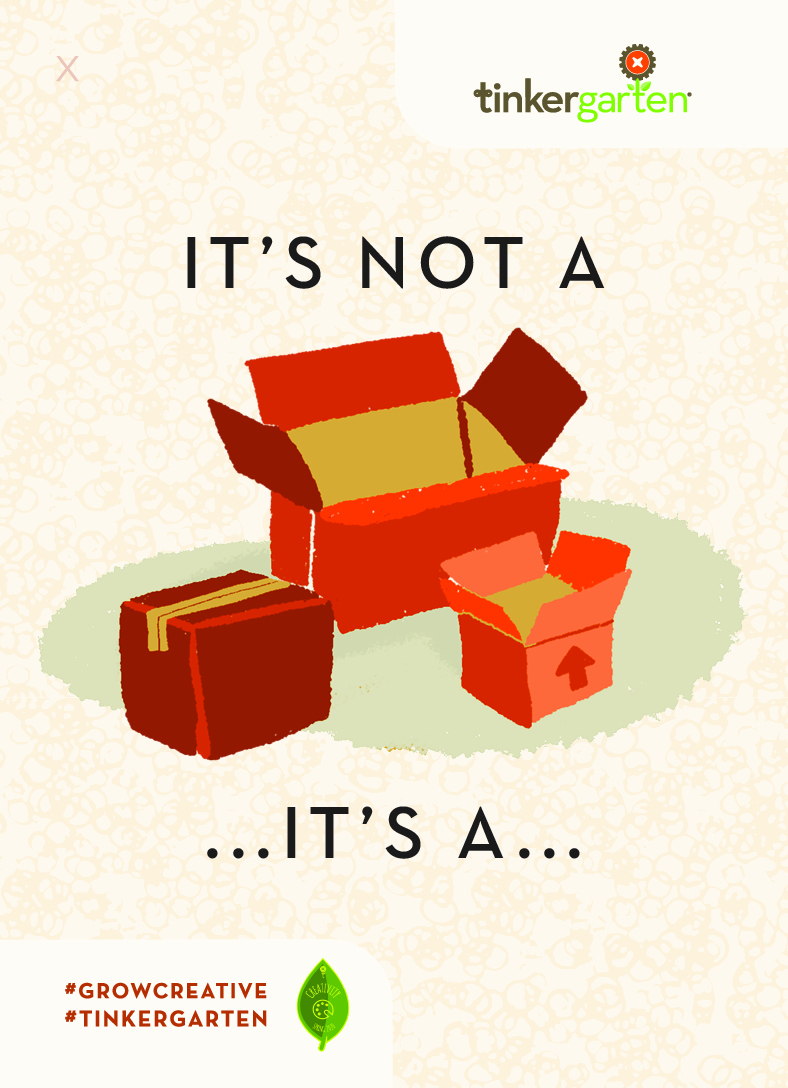

3—Play, “It’s not a ____, it’s a _____.” Start with a household object or nature treasure (sticks, leaves, stones, and feathers will all do the trick). Hold it up and ask, “Do you know what this is?” Follow up with, “Hmm...This is not a stick, it’s a....” Pause to see if your child can invent a new use for it. Or, share a few ideas of your own to get things rolling. A stick can be an infinite number of things, from a fishing pole to a shovel to a horse. For inspiration, check out Antoinette Portis’s marvelous Not a Stick and Not a Box books or come to Tinkergarten!

4—Let kids get bored and learn to work through it. Boredom can be the mother of invention and a great starting point for divergent thinking. When kids get bored, ask them open-ended questions: “What else could you do?” “How could you use the blocks, the LEGOs, your stuffed animals, in a new way today?” “What adventure can you go on?”

5—Find these moments every day. Take advantage of a trip to the grocery store, time in the backyard or even a ride in the car to test these creativity-boosting prompts.